HU2U Podcast: The Black Maternal Health Crisis feat. Dr. Shari Lawson and Victoria Revelle

In This Episode

According to the CDC, Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women, and 80% of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are completely preventable. There are a lot of reasons why Black women are at higher risk, including access to quality health care, pre-existing health issues, structural racism, and implicit bias.

Black maternal health is a serious public health crisis worldwide. What can we do to reduce this number and what are the experts doing right now to fight it?

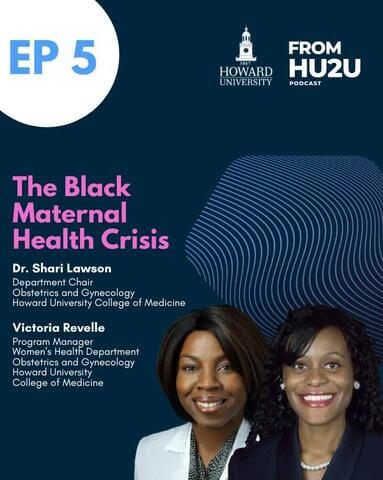

Today’s host Amber D. Dodd, Howard Magazine’s associate editor, digs into these troubling statistics in today's episode, with 2 esteemed guests from the Howard University College of Medicine. Dr. Shari Lawson specializes in Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Howard University Hospital and is a faculty member at the College of Medicine. Victoria Revelle is a program manager for the women's health and OBGYN department at the College of Medicine at Howard University.

Listen as these women discuss the systemic issues contributing to Black women's significantly higher maternal mortality rates, such as structural racism, access to quality healthcare, and implicit bias. Additionally, Shari and Victoria emphasize the importance of advocacy, trusted support systems, and exploring various birthing options.

From HU2U is a production of Howard University and is produced by University FM.

Guest: Dr. Shari Lawson and Victoria Revelle

Guest Host: Amber D. Dodd

Listen on all major podcast platforms

Episode Transcript

Publishing Date: August 13, 2024

The Black Maternal Health Crisis feat. Dr. Shari Lawson and Victoria Revelle

[00:00:00] Victoria: When we're defining this problem, Black women are not broken. The systems that Black women are in, such as where they eat, learn, work, play, and pray, are broken.

[00:00:14] Amber: According to the CDC, Black women are three more times likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women and 80% of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are completely preventable. There are a lot of reasons why Black women are at higher risk, including access to quality health care, pre-existing health issues, structural racism, and implicit bias.

Alongside constant misogynoir, Black maternal health is a serious public health crisis worldwide. What can we do to reduce this number? And what are the experts doing right now to fight it? Let's dig into it.

Welcome to HU2U, the podcast where we bring today's important topics and stories from Howard University to you.

I'm Amber D. Dodd, today's host, and I'm here with Dr. Shari Lawson, a doctor who specializes in obstetrics and gynecology here at Howard University Hospital and a faculty member here at the College of Medicine, and Victoria Revelle, a program manager for women's health and OB-GYN department at the college of medicine.

I want to give some context about this statistic. Out of 100,000 live births overall, the United States loses 21 mothers. But let's also look at the general rate in other countries, too. Canada has 11 out of 100,000. The United Kingdom has 10 out of 100,000. Japan, just four. Australia, only three. And in America, the maternal mortality rate for Black women is almost 70 out of 100,000. Not only that, it's rising in the U.S. Why does the U.S. have such a higher rate compared to other Western nations?

[00:01:44] Shari: Thank you for that question. So, there are a number of reasons why, on the whole, women in the United States are more likely to experience childbirth complications or to die in the period following childbirth. And it can be related to a number of things, including inadequacies in our maternal health infrastructure. There are also differences in our population relative to populations in some of the countries that you named before, like, Japan or Australia. We have later ages at childbirth. Many of the residents in the United States also have more chronic medical conditions, like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, for example. We have higher rates of obesity in the United States and we also have higher C-section rates.

So, on the whole, our patient population is more high risk than some of the countries that you mentioned.

[00:02:39] Amber: According to the Global Black Maternal Health Organizations, Black women in other countries are also at higher risk than their white counterparts, also at a three times the rate of white women. However, the overall rates are still far lower than the United States. The UK has a rate of 34 women out of 100,000. Australia has 10. What are your thoughts on those stats?

[00:03:00] Shari: So, I 100% agree that, once we start drilling down into each individual country's maternal mortality rate and maternal morbidity rate, we do find that there are some disparities that exist between different racial and ethnic minority groups. And so, this is due to structural racism. And so, many of your listeners might know about structural racism, but particularly as we look at it through the lens of maternal health, what does that look like?

So, I would like to refer you back to long ago as during the transatlantic slave trade, really looking at how Black women at that time, they were really viewed as inferior to Black men initially because they weren't as strong. They weren't able to, you know, plow as long or lift as heavy objects, like, during the slave labor.

But in the early 19th century when the transatlantic slave trade was, when they banned actually being able to bring more slaves over, there really was a shift because, at that point, Black women began being viewed as a commodity because this was really the only way for them to generate and replace slaves.

And so, they really started turning towards determining why some Black women were having infertility problems, why they were having difficult labors, and they really didn't want to lose any of the enslaved people at that time. But even still, when we moved into the post-Civil War era and moved into reconstruction, when slavery ended, even the most rudimentary basic care that Black women were being afforded, really only to make sure that they could produce more slaves, there really wasn't an effort to develop the care that Black women and Black men really needed.

And so, you saw the emergence of Black medical schools. There were actually seven Black medical schools that were formed during the Reconstruction period. But then, in the early 1900s, we had the Flexner Report that came out, which actually resulted in five of the seven Black medical schools closing. The only two remaining Black medical schools that remained, as you know, Howard's one, and the other one is Meharry. And really, these two institutions have been instrumental in training hundreds and thousands of Black physicians. And that's important because Black physicians are the ones that are more likely to provide care for underserved populations, racial and ethnic minorities, and they're more likely to live in those communities as well.

Other reasons that are not directly related to medicine but have a significant impact. Certainly, some of the other post reconstruction Jim Crow laws, over-policing, mass incarceration, those end up impacting women, in particular, when they have to shoulder the financial responsibilities of their household, they have added stresses related to their own partners or children being in the carceral system, mistreatment and abuse in research.

So, we can take you back to the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Many people are also familiar with how Henrietta Lacks’ own tissue was used. And so, there is fodder for this lasting mistrust that we see. You know, I could really go on, but just really wanted to give you some examples of structural racism, particularly looking at them through how they impact maternal health.

But on top of that, there are always disparities in access to care. It can be more challenging if you, for example, have a job that, is not a job that gives you time off. And we do know that racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to have those types of jobs. And then again, since they're the might be the sole breadwinner in their family, because of some of the other things I talked about with over-policing and incarceration, it may limit their ability to go to appointments or find childcare or have transportation.

The income and wealth gap makes it harder for people to afford to get care. And then once people actually do access the health system, they may get different types of care. And that's due to the implicit biases that are baked into their interactions with healthcare providers.

So, I think, overall, all of these factors can contribute to delays in receiving appropriate care. It can result in limited access to the services that they need, as well as the disparities in the quality of care that they receive.

[00:07:26] Amber: Thank you for that answer. I'm glad you were able to just give a hodgepodge of issues there. A few of my friends are Meharrians, so shout out to my Meharrian friends.

I also wanted to go off the cuff just a little bit. I think the things that we're talking about is that epigenetic factor. How much does that play a role in that quality care as well?

[00:07:43] Shari: Yeah, I mean, epigenetics also is going to have a factor. I mean, we do know even down at the cellular level, there's a phenomenon called weathering, which is where the telomeres, which are the little tips at the ends of the chromosomes, we know that, among women that live in areas that are economically depressed or they have, like, a lower socioeconomic status, the telomeres are shorter. It's related to biological stress. So, it's actually biological evidence that they're consistently placed in a stress environment.

And so, telomere length is also related to longevity. And so, we know that the stresses that our patients are experiencing, we know that it's having an impact on their health and the health of their unborn children, too.

[00:08:28] Amber: I think that rolls us right into how background plays a role. And we see that Black women with a college degree are at a 1.6 time higher rate to die from pregnancy than a white woman with a high school degree. So, it seems with even good healthcare access, the risk is still there. So, is the risk just omnipresent for Black women?

[00:08:47] Shari: It is, and I think that that's exactly right. We do know that there's some evidence that chronic stress environment that's due to structuralized racism, it does have an impact on health.

[00:08:58] Amber: And even when the issues of Black maternal health are publicized in a way. A lot of Black women have that same issue of their pain or concerns not being heard or just being waved off as common or just normal symptoms of pregnancy until it develops into a more life-threatening scenario. Can you give me some examples of how high-risk women that you've seen in these situations that could have been preventable and how they had received proper care, how that could have been solved?

[00:09:25] Shari: Absolutely. So, we see a lot of patients that have hypertension in pregnancy, and so that's a common one. Most of the time, people that have hypertension, they don't really have external symptoms. And so, when it gets to the point when someone begins to have headaches or maybe even they notice changes in their vision, their blood pressure could be dangerously high.

And so, unfortunately, sometimes a pregnant patient might say, “Oh, you know, I don't feel well today. I have a little bit of a headache.” And so, you know, reflexively, people around her or even her healthcare providers or nurses that she might interact with might say, “Well, maybe you just need to take some Tylenol. Maybe you need to lie down, take a nap, sleep it off,” rather than recognizing that headache could be a sign of something worse. And so, in particular, I'm talking about preeclampsia. And preeclampsia with severe features is a variant where it can be the blood pressure is in a very high range where it puts the mom at risk for having a stroke or having a heart attack or having it affect their kidneys. But it could just be the only symptom that they had was having that mild headache.

So, I do think it's really important that patients and their family members or loved ones are educated about the warning signs of something that could be worse. So, for them to know, “Well, if I have a headache, could I have preeclampsia?” But they may not necessarily even know to call it that. So, I think that that's part of our role as physicians and as community members, to make sure that people are aware of what the urgent warning signs are.

Other examples could be a patient having a little bit of spotting or bleeding during their pregnancy. And generally, women and other people who menstruate, they're used to having bleeding here and there, but they should know that really no amount of bleeding in pregnancy is safe. And that should prompt them to seek care because it could mean that they're at risk for having a complication or even if they're postpartum, if they're having bleeding it, but it's more than they feel comfortable with that they should seek care for that.

So, I think that what I want people to take home from this is really encouraging, if it's they themselves that's pregnant or if it's a family member or a close friend, that if it doesn't seem normal to you, or if you're concerned, that you should press it with your physician or with your midwife. And you should say, “Well, you know, I, kind of, feel a little bit off. I'm having a headache. Is there anything that's worrisome that could be associated with having a headache? Or I'm bleeding in pregnancy. Is there anything that's worrisome that could be associated with bleeding,” rather than saying, “Oh, I have a headache. It's nothing to worry about,” right? “Or I'm having a little bit of spotting. Everything's okay.”

[00:12:16] Amber: Yeah, it seems like the way that we describe the pains that we're in are, like, it's just an issue or it's just a condition. So, I'm glad that you've pointed that out there. And some states have higher rates than others, you know, whether it be urban or rural, but rural areas there may not even be a gynecologist or a physician that has that regular prenatal care available on a around-the-clock basis. How do you think that affects these Black maternal rates and Black birthing people rates of just complications?

[00:12:47] Shari: I absolutely think that some of the areas where there are maternity care deserts, the patients that are there are at a higher risk. There are many reasons why we have maternity care deserts. Some areas, there's just a lack of physicians. It's just not been easy for people to maintain their practices there.

There are also reasons, like there are states that have chosen not to expand the eligibility criteria for Medicaid. And I know that, you know, through the Affordable Care Act, it made it possible for states to have that ability. Because it's not only providing care for people during pregnancy, they need their care postpartum, they should be getting care for 12 months postpartum. And so, those are lost opportunities that do contribute to difficulty accessing the care that they need.

Additionally, some states have different rates of chronic disease, like hypertension, diabetes. You know, you're probably familiar with the term, “stroke belt,” which, kind of, goes across the lower half of the United States.

And finally, you can look at the legislation and look at how abortion care has been legislated in this country. And that also has an impact on maternal health because, when we have individuals that are at high risk and they know that having another pregnancy could jeopardize their lives, many of them are really limited in being able to seek the care that they need.

So, there are a lot of contributing factors to maternity care deserts and I 100% agree that maternity care deserts are having a negative impact on some of our patients’ wellbeing.

[00:14:25] Amber: Thank you so much. Glad that there's at least research that's being done that compares things, not only nation to nation, but state to state as well. Dr. Lawson, I want to thank you for your time today. I really appreciated it. I think Black maternal health is an issue that should be pressing for everyone, but I wanted to know how it's taking shape and form in Howard University Hospital.

[00:14:44] Shari: Yeah, absolutely. So, we have implemented some national programs at Howard to improve our maternal health outcomes. So, I'd like to direct you to the AIM bundles. So, AIM stands for the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health and Safety. AIM is basically a national organization, has representatives from many of the different health care groups, so, like the American College of OB-GYN, for example, the American College of Nurse Midwifery. I think I believe that there's about 20 or so organizations.

But what the AIM patient safety bundles do is they use implementation science to identify ways to improve the care of everyone that's receiving care at a hospital or within a health system. So, we just are in the midst of finishing our implementation bundle for severe hypertension. So, that has to do with how a patient that presents, how they're treated, meaning if their blood pressure is elevated, making sure that we have protocols in place so that we can rapidly and safely bring their blood pressures down, making sure that they have close follow-up if they preeclampsia, recognizing that we need to make sure that they're seen in 72 hours after their discharge from the hospital.

The next bundle that we're getting ready to implement is management of postpartum hemorrhage. And so, it's just important for your listeners to know that, by implementing these bundles and safety checklists, it helps to standardize the care that patients are receiving. So, whether they're at Howard Hospital, whether they're at a hospital in Michigan, Florida, or Georgia, we're all implementing the same patient safety bundles. So, it shouldn't matter where you're getting your care, but we should be all delivering the same standard of care. It's a way for us to try to reduce some of the bias that can inject itself into healthcare delivery.

I'm going to probably pass it off to my colleague here, Victoria. She's going to talk to you about some of the other programs that we're doing.

[00:16:52] Amber: Thank you so much. Hello, Victoria.

[00:16:54] Victoria: Hi!

[00:16:55] Amber: How are you doing?

[00:16:57] Victoria: I am blessed. And you?

[00:16:59] Amber: Fairly well. I wanted to also gauge, you're doing this work for Black women in a majority Black city. How do you think that work has a more of a cultural and health impact in a city like D.C.?

[00:17:13] Victoria: Yeah, it certainly is a pleasure and, I would say, really, a privilege to have the honor to do that. The way I approach this work is extremely unique. I believe that this is hard work, but I also believe that it's sacred work that we're doing. I believe that, because I am a descendant of Henrietta Jeffries, a midwife in the late 1800s, early 1900s, who delivered more than 400 babies, both Black and white, in the rural South, and became so effective at doing this, that the white women of the town stopped going to the local white doctor because they wanted their babies to be delivered by this midwife.

So, for me, I recognize that we oftentimes have roadmaps and blueprints of success and of excellence that we can, not only fall back on, but take a look at to really acknowledge and address why we're here today and the paths and ways that we can think about moving forward, which oftentimes are unique and innovative, but really allow us to understand what's going on and the ways in which we can be even more effective.

[00:18:23] Amber: What should expectant parents and mothers do to ensure that they're being heard when they don't feel right?

[00:18:29] Victoria: Yes, I would definitely say advocacy is important, being able to speak up and advocate for yourself. In addition, I would say having a trusted partner is crucial. So, having someone that you can call on and say, “Hey, I've already spoken up. I don't know if I'm being heard, or perhaps maybe you could advocate as well on my behalf to make sure that I'm receiving the rightful care that I know is due unto me as well.”

So, having a trusted partner, certainly advocating for yourself, but also considering other options and methods. So, we know that there are hospitals. We know that there are birthing centers, we know that there are new wives and doulas. There's so many resources and people to provide aid and to provide help and assistance. I think it's important to consider all of those options.

And just as important, I think it's crucial that all birthing people remember that they themselves are an important and valuable resource that they should consider, that literally, the life that they have matters and is extremely important when we're thinking about the care of Black birthing people.

Finally, I do want to mention that language is so crucial and is so important. And so, as we think about finding more solutions, I think it's important that we remember that, when we're defining this problem, Black women are not broken. The systems that Black women are in, such as where they eat, learn, work, play, and pray are broken. So, when we're thinking about how we define this, I want to be clear that we're saying this is a Black maternal health care crisis. And so, the care that is being received by Black women is something that surely, as a society, we can work on and improve.

[00:20:27] Amber: I agree.

I would love to thank the both of you for coming to our podcast today, Dr. Lawson and Ms. Revelle. This is HU2U, the podcast where we dig into today's important topics and stories from Howard University to you. I'm Amber D. Dodd, today's host. And thank you for listening. HU!